The FreeBSD Foundation is a “non-profit organization dedicated to supporting and promoting the FreeBSD Project and community worldwide.” Part of the explicit mission of the Foundation is to provide “workshops, educational material, and presentations to recruit more users and contributors to FreeBSD.” Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the folks at the Foundation launched a monthly online educational lecture series to keep FreeBSD users, developers, and donors engaged in the happenings of the Foundation and the FreeBSD project writ large during a time when face-to-face meetings were unwise.

Directors of non-profit organizations like volunteers. Almost as soon as I learned about FreeBSD Fridays, I volunteered, and I was (of course) greeted with warm acceptance. On October 22, 2021, I delivered “The Writing Scholar’s Guide to FreeBSD.”

I wrote much of the script for this lecture by merging my January/February 2021 FreeBSD Journal article “FreeBSD for the Writing Scholar” with my FOSDEM 2021 talk “FOSS for the Professional Historian.”

In keeping with my stated wishes, the words that I spoke during my FreeBSD Friday lecture are available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY). Thus, anyone is free to share and/or adapt them for any purpose, as long as I receive appropriate credit. The video recording itself belongs to the FreeBSD Foundation.

Here I share both the video recording of the presentation as it is housed permanently on Youtube and my original script. I deviated (often significantly) from the prepared script during the actual lecture. Since most of my deviations were expansions on already present themes, however, everything that matters remains present in the text. I have added several hyperlinks to assist the reader who is eager to learn more about the many software projects that I discuss.

Please enjoy, and feel free to write a comment or question below.

Deus vos benedicat,

Corey J. Stephan

The Writing Scholar’s Guide to FreeBSD

A whimsical guide to using FreeBSD as a desktop OS for multisource historical research and writing

Corey Stephan

October 22, 2021

Lifelong computer geek and Ph.D. candidate in Church history Corey Stephan has found that FreeBSD satisfies everything that he desires in a desktop operating system for his multisource historical research and writing. As Stephan suggests in his recent FreeBSD Journal article “FreeBSD for the Writing Scholar,” these needs coalesce around three themes at which this particular OS excels: documentation, stability, and security. In this talk, Stephan answers the question with which that article is likely to leave the reader–namely, ‘I see that FreeBSD has what it takes to be a superb backbone for my scholarly workflow, but what should I actually do with it?’ From building a portable set of dotfiles with ancient language legibility (through long hours of study) in mind to working with little-known but powerful command-line interface tools, Stephan cheekily explains (almost) everything that he has found to work best in FreeBSD for his unusual use case(s). Stephan hopes to inspire other academics to become Unix geeks while showing more typical FreeBSD project contributors that their labors yield fruits beyond the server and enterprise usage scenarios that tend to dominate FreeBSD’s various discussion zones. Newcomers to FreeBSD who might like to learn about using it as a desktop operating system, Unix graybeards who are hoping to learn about tiling window manager usage for the first time, FreeBSD kernel developers who would not mind receiving a metaphorical pat on the back, and anyone interested in this internally consistent descendant of primordial Unix should appreciate what Stephan has to say.

Hello, everyone. My name is Corey Stephan, and I am currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Theology at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. In this talk, I intend to give a whimsical guide to using FreeBSD on the desktop—with a special focus on historical research and writing. From building a portable set of dotfiles with ancient language legibility in mind to working with little-known but powerful command-line interface tools, I will explain (almost) everything that I have found to work best in FreeBSD for my unusual use case(s) as a historical theologian—that is, a scholar who works on the history of ideas inside Christianity.

In the process, I hope to inspire fellow academics to become Unix geeks while showing more typical FreeBSD project contributors that your labors yield fruits beyond the server and enterprise usage scenarios that tend to dominate our normal discussion zones, such as IRC and the FreeBSD Forums. Whether you are a newcomer to FreeBSD who might like to learn about using it as a desktop operating system, a Unix graybeard who is hoping to learn about tiling window manager usage for the first time, a FreeBSD kernel developer who would not mind receiving a metaphorical pat on the back for the hard work that you do, or someone who is otherwise interested in this internally consistent descendant of primordial Unix, you should appreciate at least something from what I am about to share.

Before I begin, I wish to note that I surrender rights to the video recording to the FreeBSD Foundation for posting on the FreeBSD Youtube channel and perhaps elsewhere. I will make the transcript of the talk—that is, my actual words—available on my professional website, coreystephan.com, shortly after I deliver it—entirely under a permissive Creative Commons Attribution License.

Next, since this talk is going to be on Youtube, I wish to make ‘shout outs’ to two Youtube channel operators whose work has inspired much of what you are about to see. The first is Derek Taylor of DistroTube, whose many tutorials about optimizing workflows in Arch Linux have inspired much of what I am discussing about FreeBSD. The second is [Chris], a.k.a. “RoboNuggie,” who is perhaps the only Youtube personality regularly making tutorials about FreeBSD desktop usage. If you are not already subscribed to RoboNuggie but would like to learn more about FreeBSD on the desktop, then you certainly should visit his channel.

Finally, I note that I have learned most of what I know about FreeBSD from reading every single word on every page of Michael Lucas’s Absolute FreeBSD, 3rd edition. I have a review of that volume in the most recent issue of the FreeBSD Journal. The Reader’s Digest version is that yes, Absolute FreeBSD is a success.

Alright, now, let me begin.

Perhaps it is natural that the sort of mind that thrives on piecing together minutia within one (not computer-related) academic discipline tends to be different from the sort of mind that thrives on learning to use cutting-edge technology. If all that an information technology team provides (or allows) at a workstation is either bloatware from Redmond or spyware from Cupertino, then one might (fairly) assume that nothing better exists. Each week, a typical academic must balance preparing lessons, lecturing, grading, attending meetings, and holding office hours—all while struggling to reserve blocks of time (inevitably too small) for personal research and writing.

The stereotype of the absent-minded scholar often holds true (I say while avoiding the mirror) not only because of our propensity for aloofness but also because our workdays are disorderly by institutional design. Normally, the Frankenstein Monster-esque computer setup that I notice while chatting in a windowless, book-filled office is only one piece in any particular scholar’s chaotic work life. With so much pressure to produce materials for publication, who has time to build a better computer workflow?

I think that all the traits that a scholar needs in a desktop operating system fit inside three broad categories: documentation, stability, and security.

Scholars like documentation atop documentation (atop documentation). If we cannot verify something for ourselves, then we are unlikely to trust it. This means that poorly documented operating systems cannot withstand the skepticism that is standard in the academy. Organization and documentation, in turn, go hand-in-hand. An operating system whose developers prioritize consistency is probably going to be intelligible for the person who takes the time to learn a bit about how it works. Good man pages, a clean handbook or guidebook, and a wiki that a dedicated userbase actively maintains—this trifecta is the minimum of order that a scholar’s operating system must have.

Now, scholars do not need the same kind of stability for our workstations as, say, freebsd.org needs for its servers, but we do need stability. Twice, my Ryzen-based, home-built desktop computer with 16GB of RAM has crashed because I was using about 13GB in one program to manipulate a high resolution facsimile of a medieval manuscript. On another occasion, I almost entered cardiac arrest because an update for LibreOffice’s Fresh branch rendered all of my work-in-progress dissertation chapters un-editable until I paused and realized that I simply needed to downgrade to LibreOffice Still.

Neither moment was pleasant, to say the least. Scholars work with many long, complicated documents and databases, and our success depends on as few of those failing during crunch time as possible. If tools in scholars’ toolboxes are not broken, we will not wish for anyone to try to fix them.

Security, like stability, means something else for a scholar’s workstation than it does for the kinds of environments that a system administrator or software developer probably has in mind. For a scholar, security means privacy. The best scholars share work with others for feedback and expect others to do the same with them. But we are the sort of people who tend to be quite selective about who is or who is not able to see what we are doing. Many academics work with confidential materials. Any operating system that reports what its end users are doing to someone somewhere else or that can be hacked or monitored easily is not suitable for scholarly work (or probably any kind of work except learning to be a pen tester).

Now, FreeBSD is not the only major open-source operating system with superb documentation, stability, and security (we must never overlook our siblings in the other *BSDs, for example), but it is undoubtedly one of the best. Information technology professionals often are the only people talking about FreeBSD. They (or you, I suppose) might not realize that many of the things that make FreeBSD fantastic for servers and embedded systems also make it outstanding as a desktop operating system for the writing scholar.

The documentation and organization of FreeBSD are splendid. As a scholar particularly ever in search of historical documentation, trying to find order amid a diversity of ancient voices, I find the internal coherency of FreeBSD to be downright refreshing. Even kernel building in FreeBSD mainly involves the use of human-readable, plain text configuration files. Things make sense because the people creating them aim for them to make sense. If you are already using FreeBSD, type ‘man hier’ (hier(7)) to see an initial explanation of why everything just makes sense—namely, the fact that the system’s file hierarchy itself is logically ordered.

That FreeBSD is tightly ordered holds true even down to the level of third-party packages existing in separate file directories from the system itself. Such separation helps ensure, among other things, that binary operating system updates from -RELEASE to -RELEASE are painless.

Few people are going to question the stability of FreeBSD -RELEASE versions (beside maybe some good-natured rivals with the other *BSDs). When the FreeBSD Wiki lists certain hardware as being well supported, FreeBSD most likely will not be the cause of a system crash for anyone doing (even esoteric) desktop work on that hardware. My system crashes were in a different operating system that runs on a hard-to-follow, overall messy rolling release model. I rather doubt that the same would have happened if I had been using a properly configured FreeBSD-RELEASE system and the long-term service branches of my third-party software applications.

Finally, FreeBSD is fully open and more than sufficiently secure for even the most sensitive kinds of work that we scholars do. With FreeBSD, we can trust that our intellectual property is not monitored by a suit at some hypothetical FreeBSD headquarters in Silicon Valley, and we can lock down our materials from the prying eyes of the rest of the world as much as we might need. I mean, FreeBSD even comes with three different packet filtering tools out-of-the-box. Configure one, and rest easy.

At this point, I am sure that at least a few of you are thinking: ‘Alright, Stephan. I see that FreeBSD has what it takes to be the backbone of my scholarly workflow. Great. But what should I actually do with it?’ After all, the busy scholar cannot afford to work without keeping as many tools for efficient research and writing in her toolbox as possible, and the operating system, as important as it is, is only the root tool that makes all the other tools work together, the software equivalent of a motherboard in relationship to the other hardware inside a computer.

Beside the operating system, then—which, of course, should be FreeBSD—the window manager is the most important part of the historian’s toolbox. For multisource historical research and writing, the use of a dedicated tiling window manager can improve efficiency quite dramatically relative to the use of a stacking window manager.

A stacking window manager is what comes with all mainline desktop environments, including the good old FreeBSD standbys like XFCE, LXQt, MATE, and KDE. In this setup, windows stack atop each other, typically appearing on the screen where one’s mouse cursor is when one launches a program. Most stacking window manager configurations involve using the mouse to ‘drag’ windows around the screen. Lots of clicking and dragging.

In a tiling window manager, no windows are allowed to overlap, and each window occupies all the screen space allotted to it. Manuscript facsimiles, database query tools, and other items that one might need to have opened simultaneously in various windows are placed exactly where one intends, typically by a few keystrokes. Tiling window manager usage tends to involve lots of keyboard shortcuts. When launching applications and moving their windows, one’s hands never leave the keyboard.

There are dozens of tiling window managers available for the X Window System. Generally, they can be placed inside one of two broad categories: manual and dynamic.

Manual tiling window managers, which require the user to specify exactly where each window ought to be placed based on the exact key sequence that he or she types, have an advantage with regard to precision. Yet I have found that they tend to be too tedious for multisource historical workflows.

Dynamic tiling window managers, which position windows automatically, are both simpler to use and more efficient for the kinds of tasks that we historical scholars undertake. 100% accuracy is less important for the scholar than being able to have a lot of windows open at one time without any overlap. Thus, I recommend a dynamic tiling window manager.

As for which of the many dynamic tiling window managers is best, I must remind my audience of programmers and system administrators that most of us professionally studying history are not also, well, programmers or system administrators—or, at a minimum, we are not proficient at the craft of coding. For that reason, window managers that require deep programming or scripting to configure are not viable. Indeed, the fact that so many tiling window managers require coding or scripting to use is one reason, according to my educated guess, why they are much less popular overall than the major full-size desktop environments. Is it more intuitive to setup XFCE, which feels almost exactly like Windows XP or some such thing, or dwm, which requires an understanding of at least the absolute basics of C?

Among the many perfectly fine remaining options, then, the ubiquitous i3wm and the lesser-known spectrwm (which is built mainly by some OpenBSD geeks) are noteworthy because they have human-readable, plain text configuration files. These files should be almost as familiar at first look for a historian accustomed to reading ancient lists in ancient languages as I imagine that they are for a system administrator accustomed to editing FreeBSD’s beautiful kernel configuration parameters.

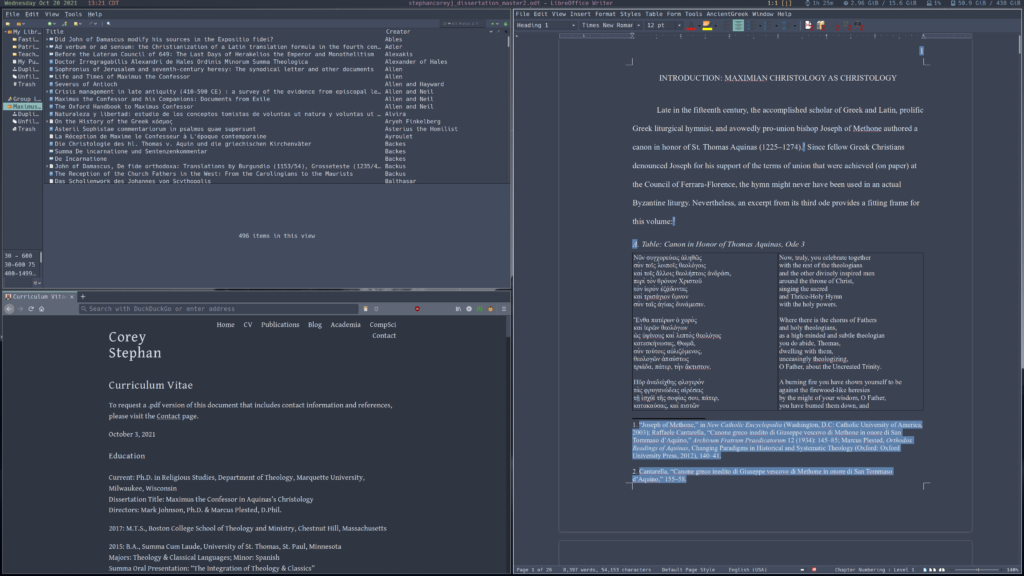

My favorite window manager overall, because it gets in my way the least of the several that I have tried, is spectrwm. That is what I am going to show today. During normal work, I use my laptop as an extension of my main desktop with the open source KVM switch imitator ‘barrier,’ which allows me to seamlessly use the same keyboard and mouse with both. For this presentation, however, I am going to keep everything as jitter-resistent as possible by sharing screenshots of my desktop in a pre-made slideshow.

Here is my blank spectrwm desktop setup on my laptop running up-to-date FreeBSD 13-RELEASE. Even on my 27” 4K monitor, I normally use multiple Workspaces, sometimes as many as 8 or 9. Let me switch the slide to show a typical Workspace 2. I would open Firefox with MOD+Shift+F, and go to my GitHub profile, ‘historical-theology‘…

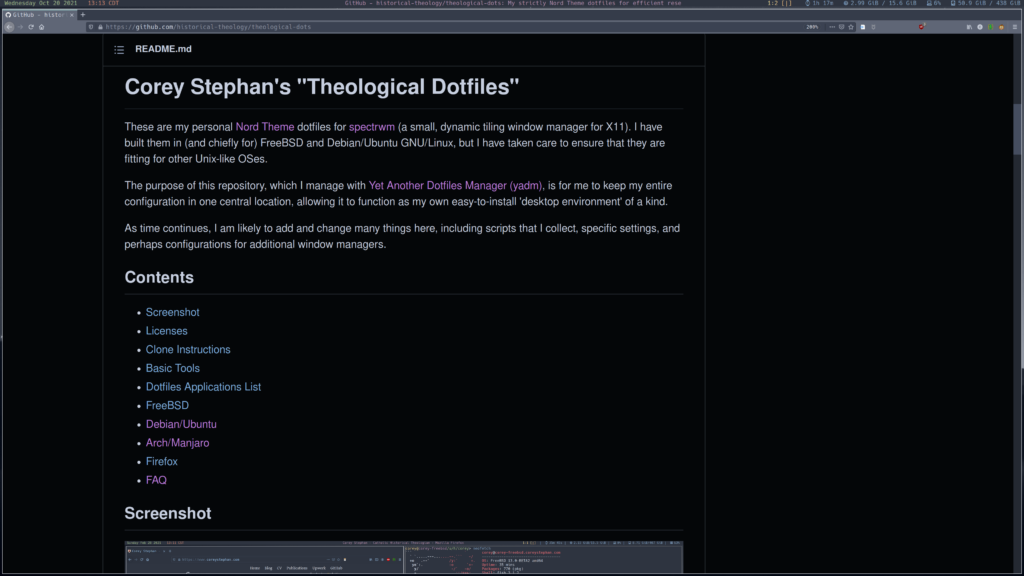

I spent years honing my workflow and learning the ins and outs of Unix-like operating systems before I finally built my own dotfiles from scratch, which I call “Theological Dotfiles.”

Why do I call them “Theological Dotfiles”? As I say at the bottom of the FAQ, “I am a professional Catholic historical theologian. These dotfiles help me theologize.”

I have found that the Nord Theme, a terminal and other computer UI color scheme about which you can read at nordtheme.com, to be extremely legible and easy on my eyes during long hours of pouring over materials, so that is what I use—to an almost fanatical degree of consistency (we academics are perfectionists). In fact, you will see that my slides for today are completely Nord Theme.

The purpose of my dotfiles repository is for me to keep my entire configuration in one central location, allowing it to function as my own easy-to-install ‘desktop environment’ of a kind. I manage the repository with Yet Another Dotfiles Manager, which runs atop and uses mostly the same commands as Git (see yadm.io), making everything dead simple.

I built my ‘Theological Dotfiles’ in (and chiefly for) FreeBSD, but I took care to ensure that they are fit with other Unix-like OSes. Because of FreeBSD’s minimalism and standards compliance—remember the ‘hier(7)’ man page to which I directed you earlier—it was almost the only logical choice for building my dotfiles to ensure broad cross-compatibility. I like Manjaro, for example, but the reality is that installing these dotfiles in even a radically minimal Manjaro Architect setup still caused some headaches for me because Manjaro has its own non-standard file locations and calls on top of its Arch Linux base, which has its own non-standard things. The Debian GNU/Linux folks seem to take standards more seriously, so everything from my dotfiles works out-of-the-box in Debian. But FreeBSD has a kind of primordial beauty to it that makes it especially useful for writing dotfiles. And, of course, once you have written your dotfiles in an OS, you probably will want to keep using it.

The center of my workflow is the glorious triad of LibreOffice, Firefox, and the citation management tool Zotero, each of which I open with a quick keystroke. All that I have to do is type MOD+SHIFT+Z to open Zotero, then MOD+SHIFT+L to open LibreOffice, and finally MOD+SHIFT+F to open Firefox. There are many ways to automate this in most tiling window managers, including spectrwm, but I find that I like to open each application window on my own—just a little less automation for the sake of being able to decide exactly what I would like to have running during a given study session.

I do all of my writing in LibreOffice Writer (Still branch) with light text on a dark background—all in the Nord color scheme. As an example, you will see the first page of my work-in-progress dissertation on the right hand side of the screenshot.

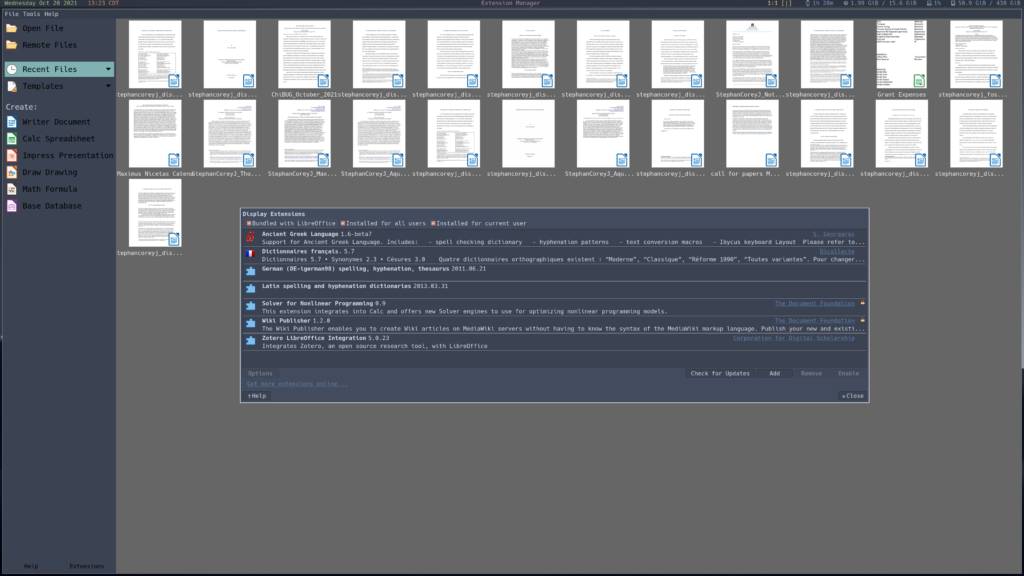

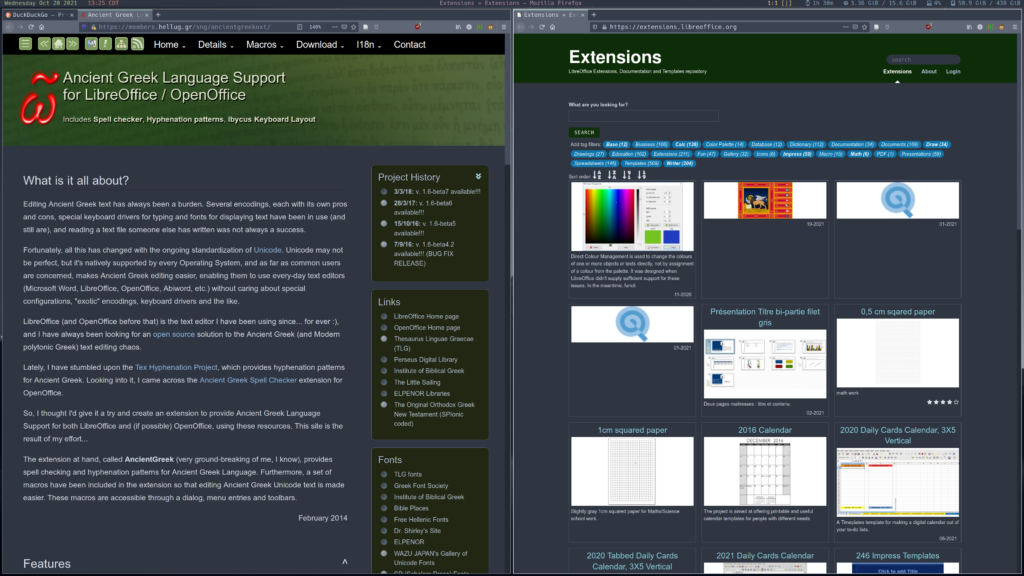

I use extensions for LibreOffice to help with spellchecking my various research languages.

The Ancient Greek extension deserves special praise for its wide array of features and decent accuracy with the range of Greek that I need to quote (from Koine to Byzantine). The Latin, French, and German spellchecker dictionaries for LibreOffice that I normally use are all quite helpful, as well. (Thousands of extensions and templates for LibreOffice are available in the official repository.)

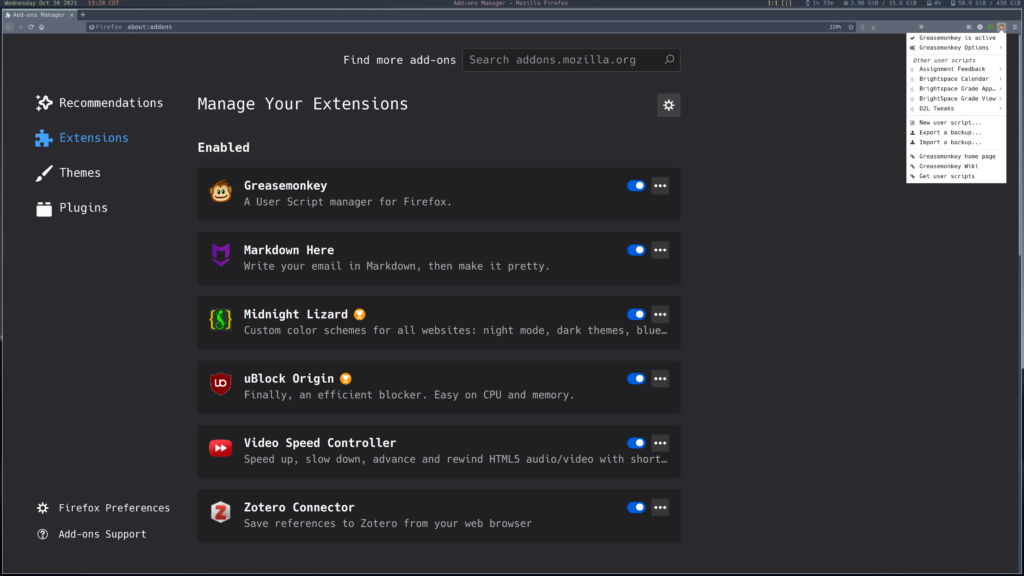

It might sound obvious to use Firefox (as probably almost everyone here does), but there is more to it when it comes to scholarship than simply using a stable, open source Web browser. Extensibility is what makes Firefox powerful for academic research and writing. I have had as many as 13 extensions and 9 userscripts installed in Firefox on my desktop, almost all of which I used to assist my work. My favorite userscripts tend to be tweaks for the Brightspace Desire2Learn (D2L) learning management system that my university uses; I wrote a blog post about optimizing work in the bloated, proprietary D2L, which you may find on my website (coreystephan.com). My favorite extensions include Markdown Here, so that I can write most HTML5 messages in plain Markdown; Refined GitHub to help me navigate resources on everybody’s favorite octocat; the official Zotero extension to pair my Web browser with my citation management tool; and LeechBlock to help me stay focused on the task at hand rather than wasting time on multimedia websites.

Zotero handles Chicago Style Notes and Bibliography (Humanities) citations quite well. The official Zotero extensions for Firefox and LibreOffice work together so smoothly, in fact, that occasionally I am able to add an entry to my dissertation’s running list of works cited from my home institution’s library website in Firefox with one click and then actually cite it in the target location with one more. Otherwise, I might have to spend a few minutes with cleanup inside Zotero, but then I do not have to worry about the particular source being cited properly for the rest of the dissertation—save odds and ends like dashes, semicolons, and italics.

Here I can both praise the FreeBSD project and make a ‘call to arms’ for its members at the same time.

First, the praise: It was a not insignificant point of frustration for me for some time that the default package builds of LibreOffice for FreeBSD did not come with the ‘Java’ flag, which is needed for most (if not all) extensions, including Zotero. Doing a custom port build of LibreOffice only to have ‘-java = yes,’ and then needing to do ‘pkg lock libreoffice’ to avoid mixups while running ‘pkg upgrade,’ was not ideal.

One day, I joined the #freebsd-desktop Internet Relay Chat room in Libera.chat. I asked if we might add the -Java flag to the package build by default. One of the main LibreOffice port maintainers, a fellow who goes by ‘fluffy,’ responded immediately that my reasoning was sound—that is, that using extensions to support advanced workflows is a major part of why someone would need to use the whole LibreOffice suite rather than a lightweight or even terminal-based alternative. By the end of that same day, he had changed the settings so that all LibreOffice package builds for all platforms would use the -java flag by default. That is what I am running now, and it is how I am using both the Zotero integration and my other advanced extensions (such as the very important Ancient Greek one).

What this shows, of course, is that FreeBSD development takes place in a friendly, responsive community. Anyone. Can. Contribute. Simply by explaining that the -java flag is essential for any sort of advanced work in LibreOffice, since it is required for extensions, I was able to move fluffy to change all LibreOffice builds in a matter of hours. The same would not happen in a humongous corporate environment or some such thing. FreeBSD is both more intimate and more collegial.

Now, the call to arms: Neither Zotero nor JabRef (another open source citation management tool with LibreOffice and OpenOffice integration) is currently available in the FreeBSD Ports tree. I have spoken with another scholar who loves the *BSD operating systems about the matter, in fact, and he agrees that the lack of either tool for any *BSD (including OpenBSD Ports and NetBSD’s cross-platform pkgsrc) is a major hurdle to getting academics to use *BSD full-time.

I am part of a FreeBSD Forum thread about Zotero in which we all collectively share information about using the Windows binary inside WINE. Yes, Zotero runs in WINE well enough, and it integrates with the native installation of LibreOffice (especially now that we have the -java flag enabled for binary packages), but it does not feel native (because, well, it is not native), and it is (like most things in WINE) both slow and prone to crashing. There is a somewhat recently expired FreeBSD port of JabRef (expired because of updates to OpenJDK) for which the information is still online.

The reality is that we need Zotero and/or JabRef, ideally both, to make *BSD desktop usage compelling for researchers writ large. If you are an industrious port maker and would like to help make FreeBSD a more compelling sell for the desktop, please consider doing one of the following: make a native FreeBSD port of Zotero; or, resurrect the recently expired JabRef FreeBSD port; or, I suppose, make a pkgsrc installation script for Zotero or JabRef that works not only in NetBSD but also FreeBSD. The FreeBSD Foundation has an open invitation to apply for grants for projects that contribute to the good of the OS; visit freebsdfoundation.org and click “Get Involved” and then “Apply for a Grant” for more information.

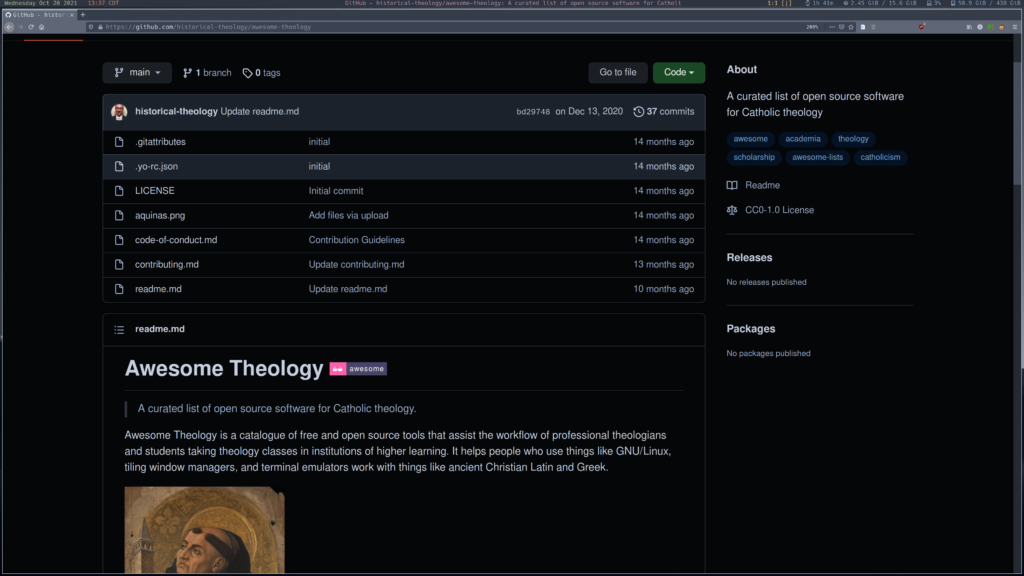

Now, let us move beyond LibreOffice, Firefox, and Zotero. Each scholar will, of course, need to use his/her own specific research tools. I have found GitHub and GitLab to be the best places to search for them. I am specifically a historical theologian, which means that I study Catholic theology in history. Thus, I often run searches to see what kinds of utilities people are writing for theology, religion, etc.

For anyone who might be interested to read what my favorite projects of that kind are, please feel free to visit the “awesome-theology” list that I have pinned in my GitHub repository (‘historical-theology’).

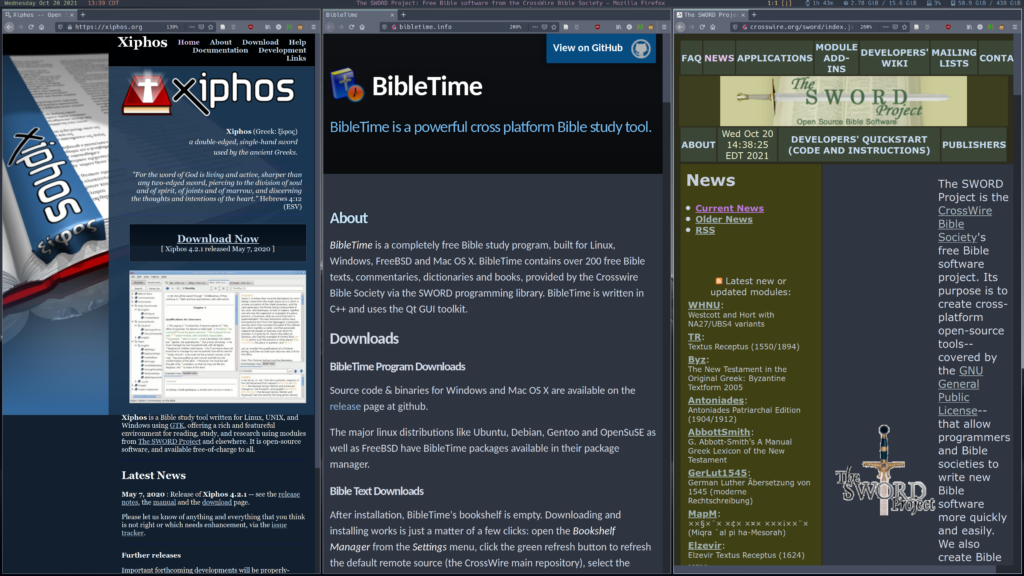

One of many things that is specific to my work is the need for aids for analyzing different translations of various parts of the Bible. I use both graphical user interface and command line interface biblical study tools.

For GUI, I use either BibleTime or Xiphos, depending on whether I am using a mostly Qt or mostly GTK setup, respectively (normally BibleTime, since I am normally using the LXQt project’s GUI tools). At the core, BibleTime and Xiphos are both GUI frontends for the SWORD Project.

Here I am showcasing BibleTime. There is nothing quite like having Greek, Latin, German, and English versions of a particular passage open in parallel for comparison with the ability to copy and paste any of the text. That all of this software is open source and text is in the public domain is, in a word, brilliant.

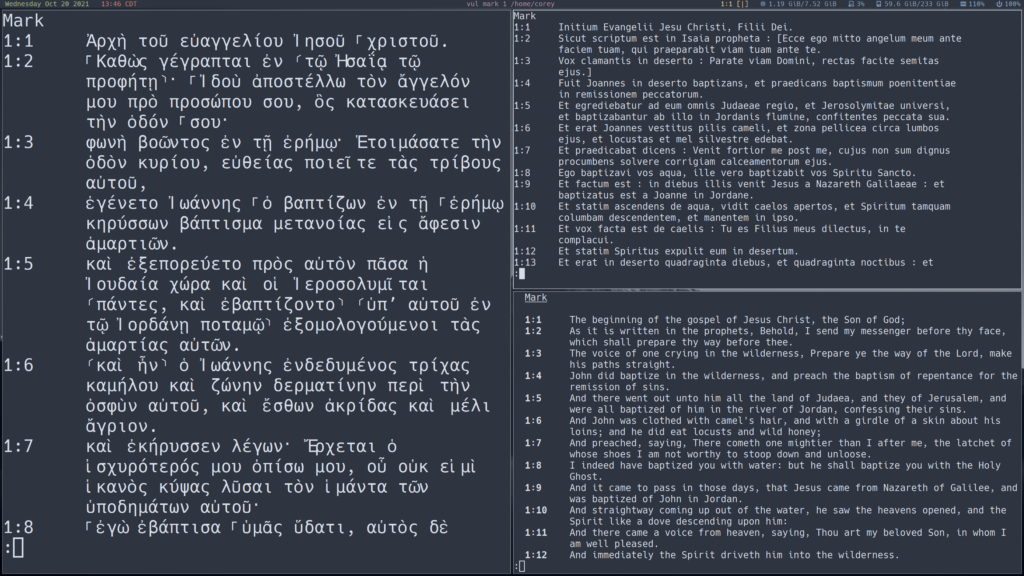

I keep the CLI Bible tools permanently open on my laptop. You will see that I have three CLI Bibles open: grb, “Greek Bible,” which contains the full texts of the Septuagint and the Greek New Testament – for example, here is Mark 1; vul, which contains the full text of the Vulgate Latin Bible [Mark 1 again]; and kjv, which contains the full text of the King James Version (English Bible) [Mark 1 again].

I keep a version of each of these 3 tools that I have modified (very slightly, by expanding the -tar commands) so it works with BSD ‘make’ instead of only ‘gmake’ in my GitHub profile (see historical-theology/grb, /vul, and /kjv, respectively). Clone those repositories, type ‘sudo/doas make install,’ and be done.

It is important to note that not all terminal emulators are up to the task of handling polytonic Greek text or other text with non-Latin characters. Among the several actively developed terminal emulators that I have tried, I have found Alacritty to handle Unicode the best. Others are more hit-or-miss.

I also make extensive use of William Whitaker’s Words, an old, trusted Latin word parsing tool that is kept alive by a dedicated group of users and developers in one central GitHub repository, mk270/whitakers-words.

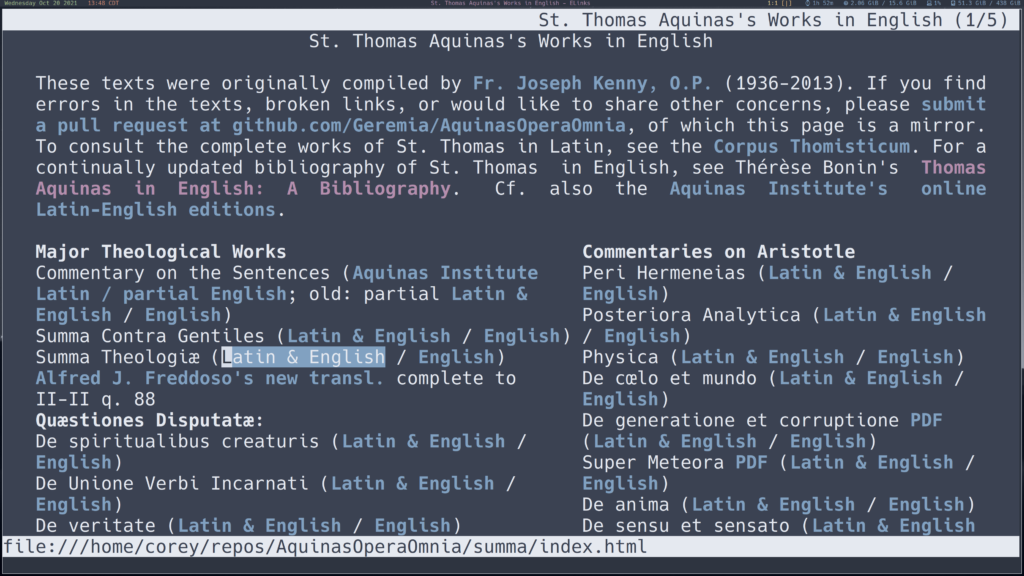

Finally, I have various shell aliases on both systems to launch what I need automatically. For example, if I need to open St. Thomas Aquinas’s opera omnia (complete works) in the elinks CLI Web browser (hosted locally), I simply type ‘tom.’ You may clone a slightly cleaned repository of that, called AquinasOperaOmnia, from my GitHub [profile]. Here is what that looks like:

For another example, if I need to open the [Freak]ing Fast File [Manager], fff, directly to the file directory in which I keep all of my dissertation documents, I type ‘diss.’ A minute saved here, a few seconds saved there, and by the end of the day, I have saved enough time to accomplish a little task that I otherwise would not have been able to accomplish.

By the way, I use the Friendly Interactive Shell, a.k.a. ‘fish,’ since it really is, well, friendly. I understand why it is that *BSD users tend to be committed to Bourne, ksh, and other classics with POSIX compliance, but just like how spectrwm is the window manager that I have found to get in the way my least, fish is the shell that gets in my way the least. Having auto-completion and helpful prompts out-of-the-box, for example, is simply splendid.

Minus the fact that I am required by circumstances at my home university to use Microsoft Teams for communication, my historical research and writing software toolkit is 100% libre. Moreover, it is highly efficient—not despite the fact that, but, rather, precisely because all of its contents are free and open source software. Being able to customize every piece of software in my toolkit means that I can make it my own toolkit, specifically optimized for my own work.

I proudly recommend FreeBSD, then, for fellow writing scholars. Install FreeBSD. Install the X Window System. Install a dynamic tiling window manager with plain text configuration like FreeBSD consistently uses, such as spectrwm or i3wm, or else—if you are not feeling quite so adventurous—a simple, traditional desktop environment (XFCE is known to work out-of-the-box on a huge range of hardware). Install LibreOffice Still and a decent citation management tool that integrates with LibreOffice and handles materials from your discipline (again, Zotero runs well enough in Wine, and I have little doubt that this talk will inspire some hacker to get working on a native option). Install discipline-specific command-line interface tools. The pkg system makes a good deal of third-party desktop software simple to install.

After all that, enjoy researching and writing with a logical, stable, and overall solid operating system. Your publishing schedule no longer will be subject to setbacks from your software.